The day the music died?

Buddy Holly, while not dead

Don McLean, in his ubiquitous 1971 megahit “American Pie”, characterized February 3, 1959 as “the day the music died”. En route to a concert via a small, chartered plane, proto pop-rockers Buddy Holly, J. P. “The Big Bopper” Richardson and Ritchie Valens were all killed when their aircraft crashed in an Iowa field on that date. It was, as they say, in all the papers. What received much less attention was the demise of the music itself. Oh, it took a while longer, perhaps twenty years, but it–along with every other original American form of music–died just the same.

Sure, pop music lives on. It always does. It’s a harmless phenomenon mostly, never aspiring to much, and only occasionally transcending its modest ambitions. Being essentially profit-motivated, it probably doesn’t deserve to be criticized in the same way as genres variously labeled as “art”, “folk”, “experimental”, “concert”, “avant garde” or any other tag implying a mission beyond simple remuneration. Rock and roll, of course, has historically functioned as pop music, as did its immediate predecessor, rhythm and blues, which continues to do so. Rock and roll became, however, something more. A cultural curiosity at the very least, but some would argue that by the late 1960’s it had evolved into something akin to art. It certainly rejected commercial implications. By 1967, for instance, the newest, edgiest rock music couldn’t be found on pop radio or in pop record stores. It ostensibly existed purely for its own sake, and seemed to acquire an audience in spite of itself.

Like all things American—even the most revolutionary, non-commercial, fringe product—if it proves to have an audience, it will attract the attention of sales and marketing types. Everyone needs to eat, and even the most outlier artists fall victim to the promises of shills and flacks. Hell, even Stravinsky had an agent. Everything, then, is “pop” music, in the sense that the full-time participants in any genre make some sort of living at it, but we think a safe delineation for more ambitious music is intent. Our contention is that the 1960’s saw the rise of something unique in modern cultural history: non-commercial pop music.

The Beatles, for instance, one of the most successful pop acts ever, finished their years together by creating music that was the antithesis of commercial in intent. They had the luxury, of course, of being the most popular entertainers in the world in mid-career. They, or anyone else in their position, could have simply kept churning out formulaic music to a willing audience, and one supposes it would have been several years before changing tastes finally diluted their popularity. Unlike any “pop” act before or since, The Beatles chose a different, more creative path by rejecting their ridiculously successful formula at the height of their popularity, choosing instead to record the groundbreaking “Sgt. Pepper” album, and then following it with increasingly oblique departures from the norm. A wag might suggest that given their unprecedented popularity, they could have released anything, from a polka album to the sound of their own farts, and their eager public would have lapped it up. The point here, however, is that they didn’t. Knowing that they would cash in regardless doesn’t diminish the quality and revolutionary nature of their effort. It’s a rare and wonderful thing, and we both celebrate and lament it. Can one imagine Lady Gaga re-inventing herself as an experimental composer in mid-career? Or Glenn Miller, for that matter?

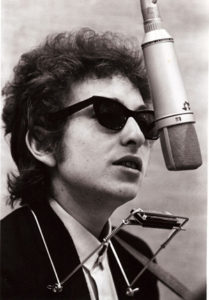

Bob Dylan, contemplating a Shure thing

The Beatles didn’t do this alone, or in a creative vacuum. The Beach Boys, riding a similar, if smaller, wave of commercial success, began experimenting with new and wonderful ideas in the mid-1960’s. Bob Dylan, already a brilliant, if fairly conventional, politically-aware folk singer, began to explore new and dangerous territory around the same time. The other “British Invasion” acts, mindful of The Beatles’ success, but at best not wanting to imitate them, began dabbling in a revival of 1940’s and 50’s American electric blues music. By the end of the decade, their personal input had created a new and vital blues genre, and it continued to evolve quickly into heavy metal and other completely original styles.

How it happened is a longer story, of course. It has anthropological and sociological implications involving race, baby booms, revolutions in media and any other number of causes and effects, but the short version is that it happened in a perfect storm of social change, political revolution and cultural maturity. The factors that make the 20th century both unique, and uniquely American, are the same factors that drove the quick evolutions of all forms of American culture, especially music. Even the British movement cited above involved almost exclusively American influence and musical vocabulary. The British themselves have always been the first to acknowledge the effect that American popular culture had on their post-war world. How it happened will be discussed at length here in future posts. What happened next, unfortunately, was probably inevitable.

By the mid 1970’s, the newest, most original rock artists were courted, marketed, and ultimately diluted artistically by impresarios and giant record companies. Any political impetus for cultural evolution, mostly the Vietnam War and the civil rights movement, was nearing its conclusion. The availability of big money and the slow demise of social revolution conspired to soften, and finally kill off, the creative surge that had taken place during the seven or eight year period from the mid 1960’s until the early 1970’s. The last great revolutionary act by rock and roll was Punk, which was a justifiably angry reaction to the fattening of the new rock and roll mainstream. Wherever there had been an “alternative” medium, money soon flowed in, and softened its artistic impact. FM radio, which rose out the need to have an on-air outlet for the music that AM radio would not play in the late 1960’s, became a victim of its own success. Record companies, who made a lot of money early on in that era by giving artists complete artistic freedom, now sought to control the product, and make it more manageable for predictable financial outcomes.

It was almost imperceptible at first. Everything that was hip and cool was still there. The inmates controlled the asylum, which seemed to be what everyone had been after all along. What people didn’t realize then was that the inmates were mostly the usual suspects, or perhaps the children of the usual suspects: accountants, A & R men in bad suits and lawyers. Lots of lawyers. Oh, they had long hair, smoked dope and talked about “change”, but it was the generation that created this ambitious music that ultimately killed it. One can get a sense of this by watching a Rock & Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremony. No one in attendance seems to get what one can plainly see from the outside looking in: that they have become their own worst nightmare. A bunch of old, fat, rich, self-indulgent celebrities, eager to wallow in their own sense of self-worth and still convinced that they constitute some sort of “counterculture”. It’s the Golden Globe Awards for old hippies.

Such nice boys: The Sex Pistols in 1977.

I would peg an official date of death for rock and roll, at least as an evolving form of music, as about 1977. That was when The Sex Pistols‘ “Never Mind The Bollocks” was released, marking the arrival of Punk into the youth culture mainstream. Punk was, and is, a legitimate genre, and was a savvy and visceral reaction to what was happening to the music at that point. Punk remained a vital form for a few years, but nothing that came after it can be considered anything more than a re-assembly of existing forms. Metal, another legit form, was already up and running by this time. Conversely, speed, thrash, death, grunge and any other subsequent “new” genre can hardly stand alone as a fundamental re-imagining of the music. Punk can, which is why it has the dubious honor of being the end. The last gasp of a noble form.

The worse news is that almost simultaneously, jazz, country and rhythm & blues were breathing their last gasps. In future posts, we’ll discuss why, and what that means for America. Until then, listen to music. Or better yet, make some. God knows, we need some.

Here’s a suggested playlist, which you can purchase tune-by-tune at Amazon:

“That’ll Be The Day” by Buddy Holly and The Crickets, 1957.

“American Pie” by Don McLean, 1971.

“All Day And All Of The Night” by The Kinks, 1964.

“Subterranean Homesick Blues” by Bob Dylan, 1965.

“Wouldn’t It Be Nice” by The Beach Boys , 1966.

Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (the whole album, unless you want to pick singles over at iTunes) by The Beatles, 1967.

“My Way” by (the) Sex Pistols, 1978.

I see no mention here of the genius of Mr. Steven Stills!

Oh, you may at some point, either as a villain or an occasional hero, but you’re not likely to see his guitar playing mentioned. At all. Ever. Besides, it getting to the point where he’s no fun anymore.